By Clément Brébion and Janine Leschke

◦ 5 min read ◦

The number of countries that are using algorithms to profile jobseekers has been on the rise since the 1990s. Algorithmic profiling aims at identifying individuals with little counselling needs, and those for whom intensive counselling and active labour market policies (ALMP) are expected to have the largest returns. The ultimate goal is to target services and thereby expenditures towards the latter. In a dual context of budget constraints and of technological innovations (which makes it possible to build and analyse large register databases), profiling algorithms are increasingly seen as an important vehicle to identify and target those unemployed who are most likely to become long-term unemployed. In an EU-funded project, HECAT – Disruptive Technology Supporting Labour Market Decision Making, we question this consensus. The goal of the project is to go beyond state-of-the-art profiling tools and develop a tool that will allow jobseekers and counsellors to get a snapshot of their labour market situation and a better sense of their labour market options.

State-of-the-art statistical profiling tools carry important shortcomings. One of them relates to the outcome category when used for defining the profiling categories. Most profiling algorithms approach jobseekers’ needs for counselling and for training programs by measuring their likelihood to remain unemployed for more than 6 or sometimes, 12 months. Usually, any type and length of employment spell is counted as a successful exit from unemployment in these models. Research on the causes and consequences of long-term unemployment (LTU) is extensive and we know that an early identification of the jobseekers that are likely to fall into LTU to take action at the earliest stage possible is key.

However, the mere focus on exits towards any type of employment is problematic. On individual grounds first, it disregards the agency of the unemployed by ignoring her lived experience of unemployment and wishes and aspirations for future labour market integration. Second, such a focus on exits without job quality in focus, can also be dysfunctional and inefficient both from the perspective of the individual and the PES as unsustainable labour market integration is likely to lead to vicious circles where people circle between (short-term) employment and unemployment.

In order to address this shortcoming, in deliverable 2.1 of the HECAT project, we discuss the scope for using job quality information in profiling and job matching tools. We develop a list of 24 items covering 7 dimensions that we see important to take into account to meet SDG (sustainable development goal) 8 on decent jobs and economic growth [1]. We do so by drawing on established job quality indices (e.g. here and here).

By putting the quality of jobs in focus, such an approach provides a more complete and sustainable vision of the labour market to the unemployed and the job counsellors and thereby increase their agency.

As we outline in the deliverable there are a number of challenges with this approach. This includes the high complexity of multi-dimensional job quality indices in view of an efficient and usable counselling and visualisation tool as well as a lack of sufficiently detailed job quality indicators on the level of occupations or sectors.

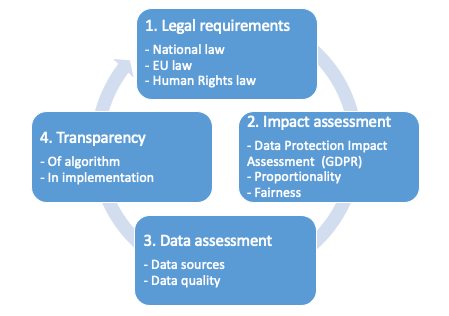

As regards data protection and data privacy, profiling algorithms also carry the risk of being in conflict with the GDPR and the case law of the European Court of Human Rights and the Court of Justice of the European Union. Importantly, these legal bases provide no ready-made ‘checklist’ as to which data can be used, nor which algorithms can be implemented. Impact assessment of algorithmic profiling or job matching tools based on algorithms must therefore take place on a case-by-case basis that takes into account the impact of the algorithm on the citizens. Governments most often disregard the need for these impact analyses and entire profiling algorithm are therefore at risk of being shut down, such as in the Austrian case in 2020.

Impact assessments should first stress the necessity of using privacy-violating profiling algorithms. This can be justified in order to comply with a legal obligation to which the public authority is subject or for the performance of a task carried out in the public interest. The proportionality and fairness of profiling algorithms must also be checked and ensured. Proportionality relates to whether the ends justify the means.

For instance, collecting and analysing data carries a cost, in terms of privacy, which must be compensated by clear gains in accuracy. One should therefore not feed the algorithm with variables that have little explanatory power. Fairness concerns imply that one should ensure that profiling algorithms are not discriminatory. This is not straightforward. Profiling algorithms classify the unemployed based on the typical behaviour observed among other jobseekers with similar characteristics. As a result, individuals from social groups that are traditionally the least attached to the labour market will be profiled as high-risk individual more often than the rest.

While this behaviour of profiling algorithms seems intuitive, research has found that among jobseekers who happen to quickly find a job, those from foreign origin are more likely to be misclassified as high-risk individuals ex-ante than natives.

The fairness condition therefore seems hard to meet for profiling algorithms. Last, profiling algorithms should only use data that is up to date and relevant and, importantly, one should ensure that jobseekers and PES counsellors who use the algorithm have a good understanding of its functioning and limitations.

Whether or not the use of an algorithm is legal must be continually assessed before, during and after development and implementation. In a working paper based on deliverable 2.2 of the HECAT project, we therefore propose a model for designing algorithms to sum up these considerations. The model is circular in order to illustrate that the assessment should be continually updated.

A proposed model for designing algorithms

“Working with not on the unemployed”

Given these shortcomings of state of the art profiling tools, our European project HECAT puts the unemployed persons and their aspirations and needs centre-stage. It aims at building a sustainable digital platform “My Labour Market” which provides both information on the estimated length of time before one exits the unemployment record and a visualisation of labour market opportunities according to one’s job quality preferences. This digital platform, to be piloted at the Public Employment Services in Slovenia, builds on extensive sociological fieldwork on unemployed persons and case workers. This tool will not sort jobseekers into profiling groups associated with specific services and labour market measures. Instead, we believe that well-informed jobseekers will make the best choices for themselves.

[1] The dimensions are: pay and other rewards, intrinsic characteristics of work, terms of employment, health and safety, work-life balance, representation and voice, distance to work.

Further readings

HECAT, deliverables 2.1: https://hecat.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Deliverable_2_1_final-2.pdf

HECAT, Deliverable 2.2: https://hecat.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Deliverable-2.2-v.7-RR_final.pdf

About the Authors

Clément Brébion, postdoctoral researcher, received his PhD in economics in November 2019 from the Paris School of Economics. His main research interests are labour economics, economics of education and industrial relations. He has a particular interest into comparative research. More recently, he started working on the EU H2020 project HECAT that aims at developing and piloting an ethical algorithm and platform for use by PES and jobseekers.

Janine Leschke, political scientist, is prof MSO in comparative labour market analysis. Her research interests comprise issues such atypical work, job quality, labour mobility and migration, youth unemployment, as well as gender. She is currently the Danish lead partner in the Horizon 2020 project HECAT, participant in EuSocialCit and one of the editors of Journal of European Social Policy.

Photo by Campaign Creators on Unsplash