By Alina Hofer, Lea Katharina Kasper & Dr. Kristjan Jespersen

◦ 5 min read ◦

When we talk about ESG, one could argue that there is a strong bias focused on climate investing, reaching net zero targets as well as good corporate governance and diversity themes. But there is much more to ESG. The “Social” dimension of ESG is hugely under explored and developed and covers under studied issues such as how companies treat their employees and care for the responsibility of their products. Still further, assessments linked to human rights codes and social impacts is only now receiving the attention it truly deserves. Although the importance of these topics is undisputed, we see that attention to particularly address the social dimension has been lacking, whereas awareness of other ESG risks has been rising immensely during the past years.

Not only is the general knowledge and focus on the social dimension of ESG limited, its overall implementation in portfolio management has not been sufficiently experimented with and addressed.

The delay to properly implement the “S” in ESG is often explained because of the challenges to quantify, assess, and integrate social factors generally.

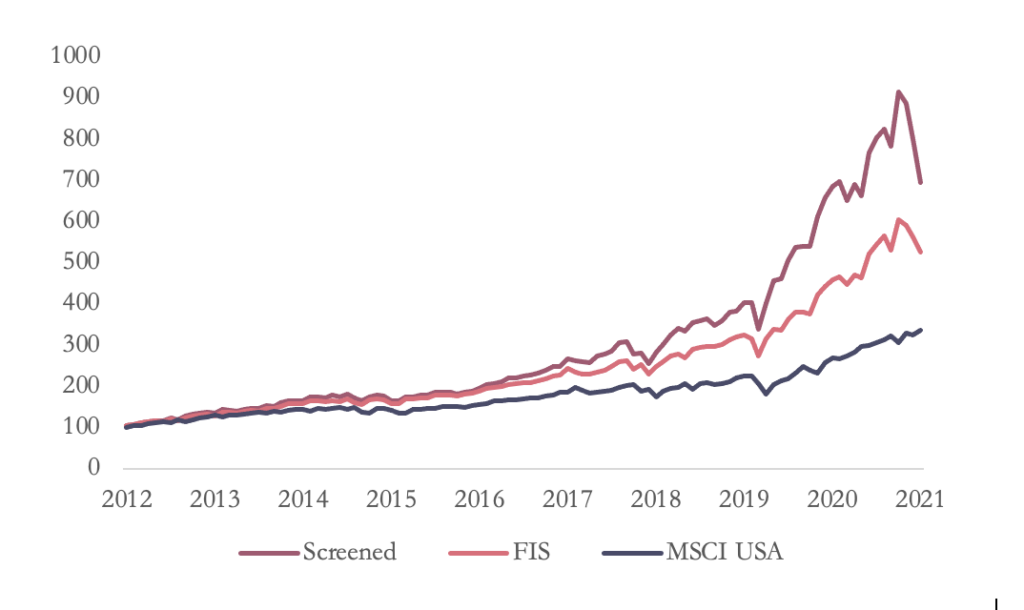

However, this argument should not be a sufficient justification for neglecting the “S” in ESG and for investigating a possible relationship between a good social rating and superior financial performance. To tackle this lack of awareness, we constructed two portfolios which integrate Refinitiv’s Social ratings based on different integration strategies and test their performance towards the market between 2012-2021.

When integrating social – or other ESG – ratings into the investment process, we find there is often disagreement on how to best consider these factors in portfolio construction. Currently, it is most common to apply screening or best-in-class strategies. These approaches aim to remove assets that do not fulfill certain criteria from a defined investment universe. Negative screening would mean to remove those companies that perform worst from the pool of assets. Inversely, an investor could also only continue with those firms who at least have a certain minimum rating. For both approaches, the portfolio weights are then allocated to the assets that remain. This is done using conventional indicators such as value, size or expected risk-adjusted returns. In our study, we, however observe a clear shortcoming of this approach: After screening out the worst 10% “social performers” and allocating weights based on a risk-return trade-off, the portfolio does not necessarily promise a higher overall ESG score than a portfolio would reach which does not consider the ratings at all. Although the portfolio yields a solid financial performance, this raises the question whether any ESG-related impact has been made with this integration approach.

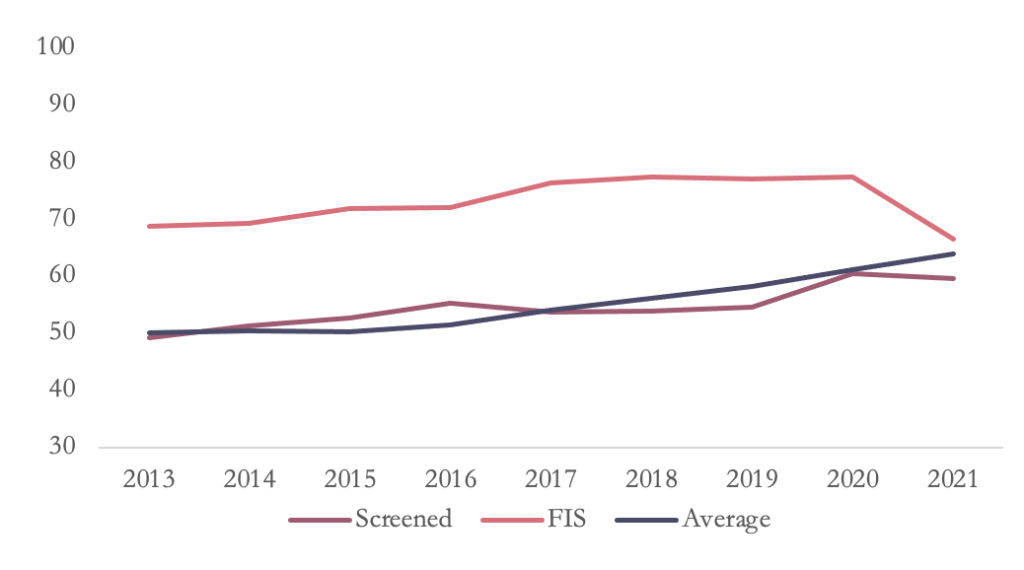

To make sure an investor can improve his exposure to assets that score well in the social dimension, we integrate the rating scores directly into the optimization problem of our second portfolio. This leads to a very different outcome on the social rating:

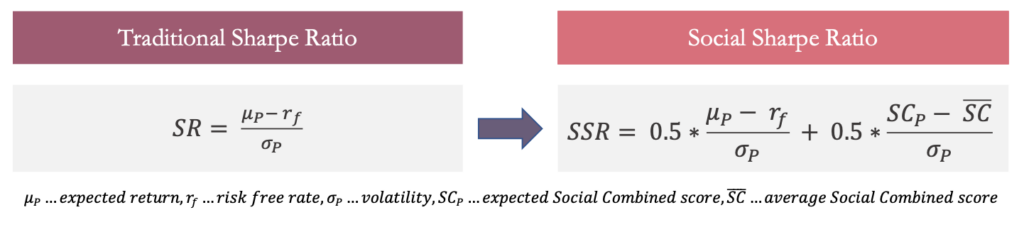

Looking closer at the mechanics of this approach, we extend the traditional Sharpe Ratio with the ESG factor, meaning to add by how much it a company “outscores” the market average. This results in the following “Social Sharpe Ratio”:

We add a fifty percent weight split, which can be flexibly adjusted towards investor preferences. And we now balance a risk-return-social trade-off. This explains why the second approach over 9 years constantly beats the market average in respect to the integrated Social factor without sacrificing any performance on the financial side. In fact, we find that in 5 out of 9 years, the second strategy would have also led to higher risk-adjusted returns measured by the Sharpe ratio. Moreover, returns were consistently higher compared to the market benchmark. This result is quite remarkable, given that it is often questioned whether investors need to sacrifice returns in order to make their investments more socially responsible.

Lastly, our study resulted in one more unforeseen twist when it comes to integrating ESG ratings. That is, the question whether we can actually trust the rating scores. To answer this, we must first understand how scores are created. Rating providers look at an immense amount of publicly disclosed information, reports and policies. And based on what company’s report, rating scores are aggregated. However, it is clear that a firm would only report on things they do well. In fact, we observe that with increased reporting, ESG scores also improve. But what about the real-life actions and impacts? Some rating providers offer a combined score, which also considers media reports on the involvement in controversial actions. As these scores are only available at an aggregate level, we calculate them on a single-pillar level using Refinitiv’s methodology, which adjusts for firm size and industry. Looking at specific examples in our portfolios, we found that the impact of such controversy involvement on the overall score could still be larger. Nevertheless, we stress that in order to have a complete picture of a firm’s ESG behavior, the impact of these controversies needs to be reflected in investment decisions.

To sum up, given the results of our research, there are three things we aim to highlight:

- It is crucial to increase investors’ awareness of “Social” matters and provide a better landscape for impact investments in this specific dimension.

- Integrating ESG ratings does not always promise a better ESG performance for the whole portfolio. Therefore, it is necessary to focus on strategies that lead to actual impact.

- Third, looking beyond the information that is disclosed by companies themselves, more attention should also be addressed to “real life actions” when making investment decisions.

About the Authors

Lea Kasper has recently graduated with a MSc. in Finance and Investments (cand.merc.) from Copenhagen Business School. Her interest and enthusiasms about sustainability and how to more efficiently integrate non-financial factors in investment decision-making contributed to her choice to further investigate this topic throughout the master thesis.

Alina Hofer has recently graduated with a MSc. in Finance and Investments (cand.merc.) from Copenhagen Business School. Being passionate about creating impact through ESG-aligned investments, she was excited to further focus on her interest in this field throughout the master thesis.

Kristjan Jespersen is an Associate Professor at the Copenhagen Business School. He studies on the growing development and management of Ecosystem Services in developing countries. Within the field, Kristjan focuses his attention on the institutional legitimacy of such initiatives and the overall compensation tools used to ensure compliance.

Image source: SustainIt