By Margherita Massazza & Dr. Kristjan Jespersen

◦ 4 min read ◦

From the outset, this blog post takes the perspective that behavioral finance is required to assess the perceived tension in sustainable investing (SI). Our work investigates the extent to which sustainability considerations are included in investment decisions, and the drivers behind SI approaches.

Sustainability is increasingly integrated in financial markets, with the acronym “ESG” (Environment, Social, Governance) becoming an all-encompassing term widely used in all phases of the investment process. According to a recent global review, sustainable assets [1] reached USD 35.3 trillion at the end of 2019, representing 35% of total professionally managed assets, and they are set to grow further in the coming years. Yet, despite its growth and the positive sentiment associated with it, there is an inherent tension in sustainable investing.

This tension stems from the apparent disconnect between the theoretical assumptions of classical financial models, focused on risk and financial returns as the predominant determinants of investment decisions (e.g., Capital Asset Pricing Model, Modern Portfolio Theory, etc.), and the empirical evidence of SI, where portfolio allocations are affected by non-financial aspects like personal values and social pressures. How can we make sense of this tension?

Usually, the contradiction is formulated in terms of a tradeoff between financial returns and ESG impact: in order to achieve one, investors must forego the other. However, this view is still rooted in a traditional finance perspective, according to which including ESG considerations or seeking a non-monetary impact comes at the expenses of returns.

There needs to be more nuance in how sustainable investing decisions are investigated and assessed. Given the pervasive and engaging nature of ESG issues, sustainable investing is likely shaped by internal and external forces that go beyond the financial-vs-impact debate. By acknowledging the role that cognitive limitations, biases, and the external context play for investments, behavioral finance allows to capture the financial impact of factors that tend to be overlooked in mainstream financial theories.

Under this perspective, the authors carried out a study based on primary data from European retail and professional investors. It focused on two main questions:

To what extent are sustainability considerations included in investment decisions?

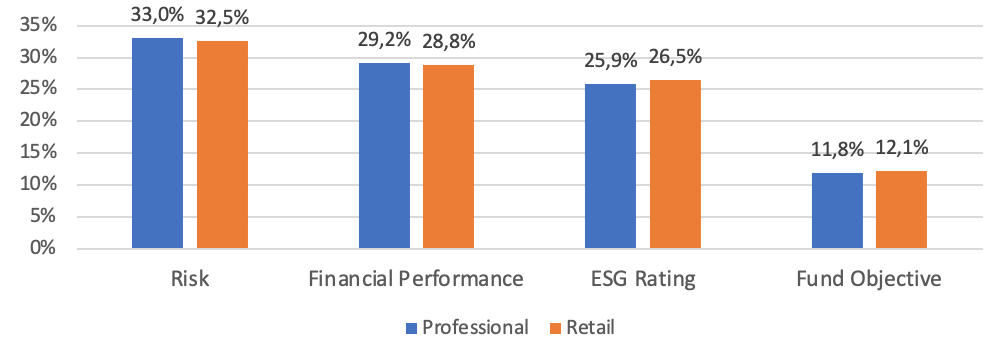

Firstly our analysis broke down the relative importance of four attributes for the investment choice, i.e. the relative weight (expressed in percentage) that each characteristic exert on the investment decision. Sustainability attributes carry a relative importance of about 38%, with ESG score displaying a 26% relevance, and the investment’s end objective a 12% relevance. Taken together, these parameters display a larger role than standard financial attributes of risk level (relative importance of 33%) and expected returns (relative importance of 29%) (Figure 1). The results confirm the significance of ESG aspects for a well-rounded assessment of an investment, arguing against the traditional perspective of risk and returns as the sole determinants of investment choices.

What drives investors to invest sustainably?

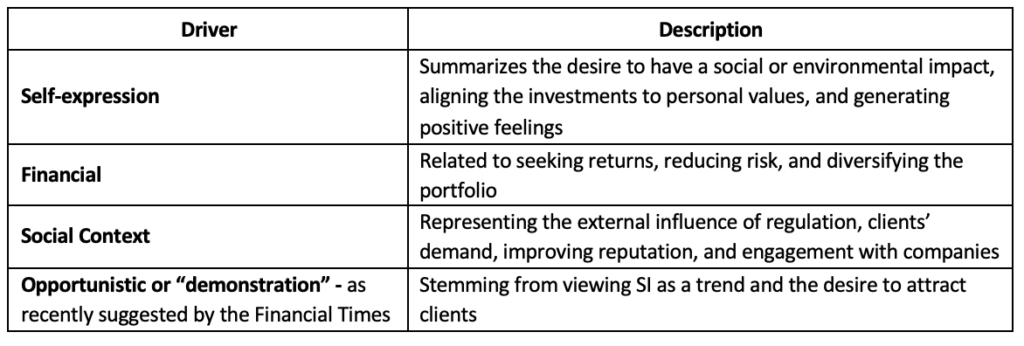

Secondly, we identified the main tendencies leading investors to engage in SI. Starting from a set of 16 heterogeneous motives, 4 main drivers emerged: a desire for self-expression, a financial-strategic rationale, the influence of the external context, and an opportunistic motive (Table 1). These drivers depict SI as a multifaceted phenomenon that unfolds along various dimensions, and not only on the financial and impact layers. They propose a novel perspective to think about SI, which takes into consideration how endogenous (e.g., alignment with values) and exogenous (e.g., role of regulation) forces may affect investments.

How can the findings help us better assess sustainable investing?

This analysis shows the extent to which ESG aspects are integrated in investments, confirming their importance for investment choices. It also shows the multidimensionality of SI drivers, which eschews the rigid perspective of traditional finance and accounts for the impact of relevant internal and external factors.

With this understanding, it is possible to formulate practical insights for industry participants to address the current challenges of SI. In fact, there are concerns related to the over-inclusion of sustainability in investment decisions at the expenses of fundamental financial analysis, which may lead to mispricing, inflated asset evaluation, and potentially an “ESG bubble”.

- Standardize definitions and improve sustainability communication. Social context emerged as one of the drivers of SI, and regulators have a strong role to play in harmonizing the meaning of sustainability in finance. Legislative and non-governmental bodies are working to overcome the lack of standard definition and frameworks in SI – e.g., via the European Union’s Sustainable Finance strategy. Their effort to create a common vocabulary and shared understanding of what SI entails will help to align incentives, concepts, and strategies. In parallel, the financial-asset supply side (e.g., fund providers, financial advisors, etc.) should communicate clearly and extensively on the sustainability aspects of financial products. Given the importance of ESG characteristics for investment choices, this will ensure investors have reliable and trustworthy information to guide their investments. Together, the agreement in terminology and the availability of sustainability information will reduce the possibility for misinformation and opportunistic tendencies to sway investment decisions.

- Recognize the existence of complex drivers behind sustainable investment decisions. Investors, both professional and retail, should evaluate how different motives affect their investment choices. Knowing that multiple drivers exist will ensure that investment are aligned with goals, limiting the influence of irrationality and misinformation. This will not only benefit investment strategies, but also curb counter-productive results such as the emergence of an ESG price bubble. To explore what drives investor’s decisions, an ad-hoc survey could be submitted ahead of opening investment accounts, mirroring the logic of the MiFID directive. This may have positive effects, such as involving more retail investors in sustainable investing [2].

- Finally, consider adopting a behavioral approach when studying sustainable investing. The flexibility of behavioral finance may allow to grasp further insights and help to think about this timely topic in a novel way.

References

[1] The Global Sustainable Investing Alliance (GSIA) considers defines “Sustainable” all assets that integrate ESG factors in the analysis and selection of securities. More detail in their latest global report.

[2] Retail investors still face barriers to fully engage in SI: the topic is investigated in the paper “Investment Barriers and Labeling Schemes for Socially Responsible Investments” by Gutsche and Zwergel (2020).

About the Authors

Margherita Massazza is a CBS and Bocconi graduate in Economics of Innovation, with a focus on Sustainability. Her research investigates the links between traditional investments and behavioral finance to understand how sustainability decisions unfold. She is currently working in the Foresight team of AXA, an insurance company, where she studies the role that corporations will play in the future and how the concept of sustainability will evolve.

Kristjan Jespersen is an Associate Professor at the Copenhagen Business School. He studies on the growing development and management of Ecosystem Services in developing countries. Within the field, Kristjan focuses his attention on the institutional legitimacy of such initiatives and the overall compensation tools used to ensure compliance.