By Clément Brébion

◦ 3 min read ◦

Despite an unprecedented worldwide decline in mortality over the last century, a substantial income gradient in life expectancy persists within most countries. In the US for instance, the 1% richest men have a life expectancy at the age of 40 that is 15 years larger than the poorest 1% (difference of 10 years for women) and this spread is currently increasing. In France (on which this blog post is based), the income gradient is of a similar size despite a more egalitarian access to health care.

Pandemics likely amplify this spread because they reveal latent inequalities in individual health capital and because they spread differently across living environments. Our recent study reveals that the COVID-19 crisis, which epitomizes such massive mortality shock on a worldwide scale, is not an outlier in this respect.

A few definitions

We analyse the impact of COVID-19 on mortality inequalities over the whole year 2020 in France, one of the most severely hit country in the world. We use comprehensive registered data, allowing us to study the evolution of mortality as well as the income level of each municipality of metropolitan France. Given the unreliability of public data on deaths attributed to COVID, we focus on excess mortality occurring in each municipality, defined as the deviation in 2020 all-cause mortality with respect to the average of 2019 and 2018. The link between poverty and morality related to the epidemic is thus analysed by comparing excess mortality between ‘rich’ and ‘poor’ municipalities, where ‘poor’ is defined as belonging to the poorest 25% of municipalities (‘Q1’ hereafter).

Two waves that have affected more the poor municipalities

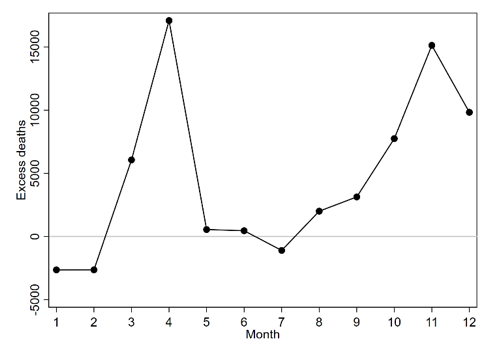

Figure 1 below shows that, as in many European countries in 2020, France has been hit by two distinct waves that peaked in April (17,000 extra-deaths) and November (15,100 deaths), respectively. Each time, a lockdown was implemented at the national level to reduce the spread of the disease (March, 17 to May, 11 & October 30 to December 15). The first lockdown was the most stringent and has seemingly worked best to reduce casualties to COVID-19.

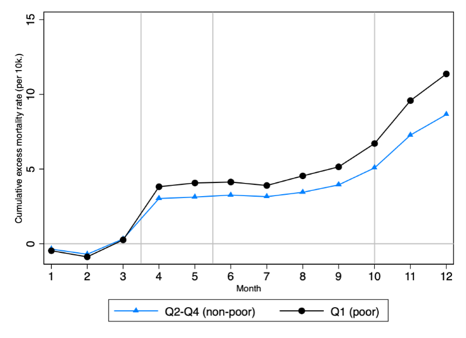

Figure 2 shows the distribution of excess mortality across municipalities according to their income. Each month, the figure shows the average number of abnormal deaths that occurred since the beginning of the year in each group of municipalities (per 10k. inhabitants). While no specific pattern can be seen over the first three months of 2020, a marked difference between the two groups of municipalities appears in April (wave 1), that further grows as the second wave takes place (October-December).

In-depth analyses tell us that excess mortality in poor municipalities was 30% larger than in non-poor municipalities in 2020 (2.6 more extra-deaths per 10k. inhabitants). Our research shows that this spread directly relates to COVID-19 and is not explained by differences in the geographical localisation, in the share of old-age inhabitants or in the life conditions under the lockdown between rich and poor municipalities.

The fact that the income gradient uncovered during the first wave is not compensated during the second wave, but rather reappears with regularity every time the epidemic returns must be emphasized. One can indeed show that the income gradient is the strongest in areas that got most affected by COVID-19 in 2020. If further epidemic waves occurred – and some signs suggest that it has already started in France as well as in several other countries – our result suggest that, once again, the poorest municipalities will suffer greater losses.

Worse housing conditions and higher exposure through employment

What are the main differences between poor and non-poor municipalities that explain the income gradient in Covid-19 mortality? Our analysis highlights the key mediating role of labour market and housing conditions, in line with the idea that local factors are important determinants of the spread of epidemics. More specifically, the larger share of essential workers and of overcrowding housing almost fully explain the income gradient in COVID-19 related mortality. Interestingly, labor-market exposure remains an important determinant of COVID-19 mortality across both waves, while the role of housing conditions decreases over time, probably because the second lockdown was less stringent.

Our work shows that the current health crisis amplifies already existing socio-economic inequalities. It also suggests that public policies aiming at limiting its effects should primarily focus on the poorest municipalities, notably by protecting workers as much as possible in the short term and by improving housing conditions in the medium term.

References

Brandily, P., Brébion, C., Briole, S., & Khoury, L. (2021). “A Poorly Understood Disease? The Impact of COVID-19 on the Income Gradient in Mortality over the Course of the Pandemic” , Working Paper, n° 2020-44, Paris School of Economics.

About the Author

Clément Brébion joined CBS in September 2020 as a postdoctoral researcher. He received his PhD in economics in November 2019 from the Paris School of Economics. His main research interests are labour economics, economics of education and industrial relations. He has a particular interest into comparative research. More recently, he started working on the EU H2020 project HECAT that aims at developing and piloting an ethical algorithm and platform for use by PES and jobseekers.