By Rikke Rønholt Albertsen

◦ 3 min read ◦

The sustainability contributions of business are under increased scrutiny in society. Observations of greenwashing, blue-washing, corporate hypocrisy, and decoupling suggest the existence of an intentional or unintentional gap between espoused CSR strategies and actual sustainability outcomes at the societal level. In other words, there seems to be more “talking” than “walking”.

This has inspired a growing concern in parts of the CSR research community that maybe we have been asking the wrong questions. Is it possible that in some ways we are contributing to this gap between strategy and impact?

Next year, an entire subtheme of the annual European Group for Organisational Studies (EGOS) conference will be dedicated to “Rethinking the Impact and Performance Implications of CSR”. This subtheme will address the tendency in CSR research to focus on outcomes at the organisational level without analysing impacts at the societal level.

There are valid reasons for limiting the scope of CSR research in this way: from an organisational performance perspective, many of the traditional success criteria for CSR policies—such as strengthening legitimacy, market position, and employee satisfaction—do not require data to be gathered on sustainability impact from a societal perspective.

However, the urgency and magnitude of the current global crisis related to climate, biodiversity, and social inequality fuels the expectation that corporations should acknowledge their role in creating these crises and take decisive action to be part of the solution. From this perspective, one would expect CSR research to provide knowledge of how, when, and why CSR policies and practices truly contribute to solving sustainability challenges. Yet, as a review of current CSR literature shows, this is rarely the case [1].

So what constrains CSR researchers from addressing this impact gap? In the following, I will highlight two interrelated mechanisms that have emerged from my research.

1) Sustainability impact is non-linear, systemic, and complex.

The problem with measuring sustainability impact is that it does not conform to conventional systems of measurement and reporting. Company CSR reports primarily provide key performance indicators linked to resource use per unit of production or list company policies and protocols to ensure compliance with various sustainability standards. In general, companies tend to (self) report on the successful implementation of their (self-imposed) CSR strategy, which happens to align with existing business objectives. However, as dryly noted by former environmental minister and EU commissioner Connie Hedegaard: the need for CO2 reductions is not relative; it is absolute! The melting Arctic poles do not really care that a company has made an effort to reduce its relative emissions if the net result is still more CO2 [2].

The negative impact on ecosystems is subject to irreversible tipping points where effects compound and accelerate. Thus, the societal impact of a sustainability policy or protocol cannot merely be assessed at the organizational level. It must be traced up and down the value chain and checked for unintended systemic consequences and hidden noncompliance [3]. Think of ineffective emission off-set schemes or families impoverished by bans on child labour. Ultimately, being “less bad” does not necessarily amount to being good.

2) Researchers do not have the necessary information.

Analysing the societal impact of corporate CSR policies and practices is a highly resource intensive task, which requires an entirely different set of research skills and data access than traditional organisational research. Instead, researchers most often opt to evaluate sustainability performance through estimations, perceptions, and narratives offered by company staff in surveys and interviews [1]. This data is context specific and prone to subjective biases, making it difficult to draw objective conclusions about societal impact.

Consequently, because there is so little existing knowledge of the link between CSR initiatives and societal impact, the CSR contribution of corporations is primarily assessed based on compliance with reporting standards and commercial rating initiatives such as the Dow Jones Sustainability Index [4]. This, for lack of better options, becomes the go-to objective indicator of CSR performance used by CSR researchers. Through this self-fulfilling circular logic, these indicators are used to identify CSR high performers for research on best practice. CSR research thus potentially perpetuates the perception of what successful CSR policies and practices look like—all without examining the societal impact of these practices.

Is this a problem?

Just as corporations increasingly realise that addressing CSR issues is no longer optional, we as CSR researchers may need to move beyond asking how, when, and why corporations engage with sustainability and begin asking how, when, and why corporations contribute to sustainability. If we do not, we risk losing our relevance when corporations look to academia for guidance on how to design and implement CSR strategies based on maximum impact rather than just maximum compliance and minimal risk.

We are challenged to expand our field of enquiry and be innovative when assessing how the observed means ultimately align with desired ends. This will require forging research alliances with new knowledge fields and establishing relationships with new groups of informants beyond company employees. The first step, however, is to rethink the questions we ask.

Further reading

[1] J.-P. Imbrogiano, “Contingency in Business Sustainability Research and in the Sustainability Service Industry: A Problematization and Research Agenda,” Organization & Environment.

[2] C. Hedegaard, “Farvel til ‘logofasen’ -nu har vi set nok grønne slides,” Berlingske, 2020. [Online].

[3] F. Wijen, “Means Versus Ends In Opaque Institutional Fields: Trading Off Compliance And Achievement In Sustainability Standard Adoption,” The Academy of Management review.

[4] M. Zimek and R. J. Baumgartner, “Corporate sustainability activities and sustainability performance of first and second order,” 18th European Roundtable on Sustainable Consumption and Production Conference (ERSCP 2017).

About the Author

Rikke Rønholt Albertsen is a PhD Fellow at the Department of Management, Society and Communication at Copenhagen Business School and a member of the multidisciplinary CBS Sustainability Centre. Her research focus is on exploring and understanding gaps between the espoused sustainability objectives of corporations, and their actual contribution to sustainability. She has a background in consulting at Implement Consulting Group and in sustainability advocacy as co-founder of Global goals World Cup.

Photo by Emily Morter on Unsplash

Transportation matters, Pic by

Transportation matters, Pic by  Organic Cotton Yarn, Pic by

Organic Cotton Yarn, Pic by

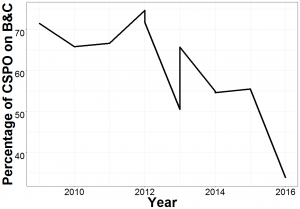

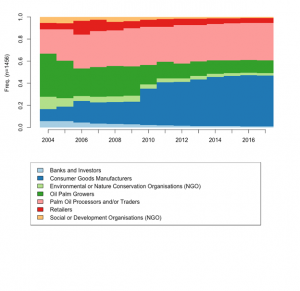

Figure 1: Composition of RSPO membership, by year (RSPO Website Data). Credit: Mikkel Kruuse and Kaspar Tangbaek.

Figure 1: Composition of RSPO membership, by year (RSPO Website Data). Credit: Mikkel Kruuse and Kaspar Tangbaek.