By Anna Sophie Hauge, Marie Haadem and Meike Janssen

◦ 4 min read ◦

Innovation fosters creativity and generates growth – especially in times of crisis. The foodservice industry has been hit extremely hard by COVID-19 and the corresponding restrictions and lock-down measures. While many businesses in the foodservice industry struggled to survive, some took the opportunity to innovate. The question is then, what drove businesses to innovate in the middle of the crisis?

Drivers of firm innovation and the outcomes differ from case to case, however all can be connected to overarching themes. The external shock of the COVID-19 crisis is undoubtedly one such theme which has created new environments for supply and demand within the foodservice industry.

…times of crisis may provide an opportunity to develop dynamic capabilities more quickly than good financial times. A possible explanation is that ‘dynamic environments’ are needed to deploy dynamic capabilities

Alonso-Almeida et al., 2014

In the spring of 2021, we interviewed five courageous food-entrepreneurs, all using innovation as a survival mechanism throughout the crisis. We used John Bessant and Joe Tidd’s 13 drivers of innovation as the starting point to have a closer look into five small- to medium-sized innovative companies from Copenhagen and Oslo: a gourmet pizza takeaway, an online grocery delivery, an online fruit and vegetable delivery, a vegetarian takeaway, and a café takeaway.

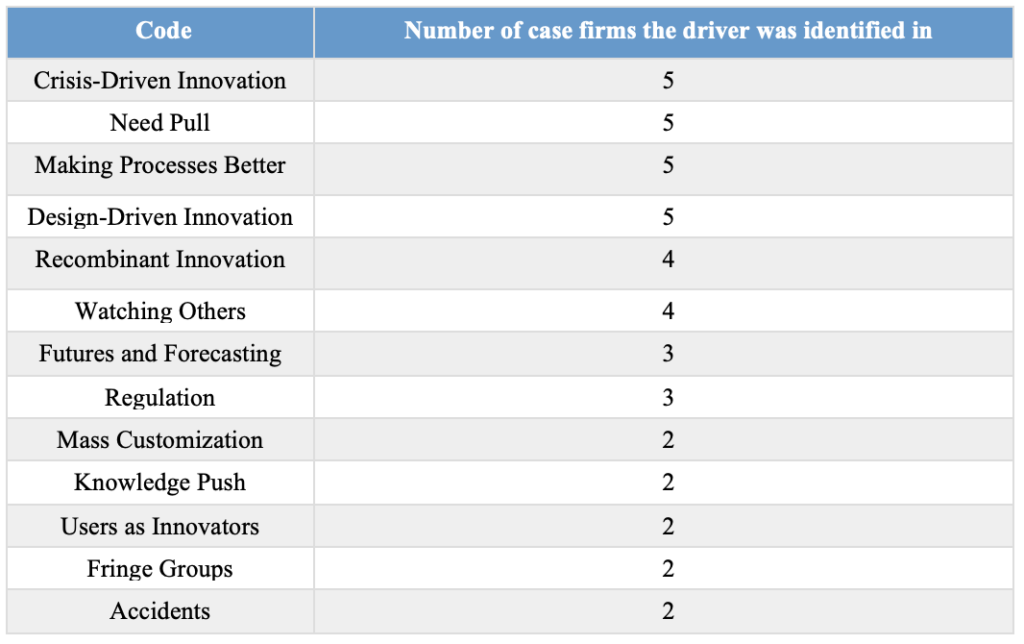

Besides the crisis itself being the most powerful driver of innovation, the need for change in the way people consume and offer food services proved to inspire numerous innovative measures (See Table 1). The trends and environments created by COVID-19 inspired new processes within our pre-existing case firms. For the three firms established pre-COVID-19, a large focus was put into the implementation of contactless home deliveries.

Additionally, we found that the crisis even triggered the innovation of completely new businesses. The two we interviewed exploited the rapidly changing environment to meet new needs, employing pandemic-friendly formats to deliver their services. An example is the highly integrated use of Instagram as a food ordering and communication platform. Innovation of business processes and products became survival means for our firms within the foodservice industry, as it helped them keep up with new consumer needs in the context of the pandemic. At the same time, these changes elevated the firms’ value propositions due to the new operating circumstances imposed by COVID-19. Products and processes were adapted to the COVID-19 trend of ‘support your locals’ throughout lockdown, through the integration of local suppliers and products. Innovations in relation to such trends helped target important social values during the pandemic.

Many of the innovations within the case companies originated from the necessity of minimizing the spread of the COVID-19 virus. Changes to the physical spaces of the foodservice firms and higher focus on contact through digital channels are examples of measures taken.

Characteristics of Success

Four out of the five firms were small in size. Each firm utilized collaborative relationships in the development of their products and services during the pandemic. Congruently, these firms explored new market opportunities; both in the expansion and adaptation of product lines and services, but also starting completely new businesses. Another characteristic was the integration of technology, such as online ordering and social media communication. We also found that the firms innovating during crises did not compromise on costs in their innovations. Ultimately, these characteristics developed and supported the firms’ crisis-driven innovation. It was also recognized that the pre-existing firms were innovative also before the crisis, which helped facilitate their innovation in times of distress. These characteristics are identical to those found in companies that innovated during the financial crisis in 2008.

Two additional characteristics were identified in the firms; firm flexibility and targeting niche segments. High flexibility was identified within the case firms, introducing options for pre-ordering, and thereby allowing for efficient and sustainable use of resources. Firm flexibility was also created through the use of digital modes of operations like online communication platforms and ordering systems. Lastly, four of the case firms have niche and urban customer segments. They target a trendsetting, educated urban-elite, all living in central Copenhagen or the West End of Oslo. Both the firms’ business models and unique selling propositions are non-typical for the given industry. Having such target groups and trend-setting concepts is seen to have enabled successful innovations. These two firm characteristics arguably provide the necessary infrastructure for the innovations’ success and are recognized to be essential for firm survival in times of crisis.

In the end

It is inspiring to see that times of crises can inspire people, and that courageous steps are being rewarded in a dynamic environment with open-minded customers. However, not all cafés and restaurants were as lucky as the ones in our study. Now that restrictions are no longer in place, the foodservice industry deserves our support, and you deserve to regularly treat yourself to a nice dinner or lunch.

About the Authors

Anna Sophie Hauge is studying her master’s in Finance and Strategic Management at Copenhagen Business School. Outside of her studies, she is currently working as a commercial student analytic at Løgismose, a Danish food brand, focused on quality and ecology.

Marie Haadem is currently finishing her Master’s in Management at IE Business School in Madrid, specialising within Finance and Investment. She will be joining Citigroup this July as a Banking Analyst for the EMEA Banking Analytics Group in Spain.

Meike Janssen is Associate Professor for Sustainable Consumption and Behavioural Studies, CBS Sustainability, CBS. Her research focuses on consumer behaviour in the field of sustainable consumption, in particular on consumers’ decision-making processes related to sustainable products and the drivers of and barriers to sustainable product choices.

PhPhoto by Kai Pilger on Unsplash