By Johanna Jarvela

◦ 2 min read ◦

Last March European parliament gave a proposal to create mandatory Human Rights Due Diligence directive. The aim is to prevent human rights and environmental harm in a more efficient way, through regulation. The commission proposal is based on the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and has three core elements: firstly, companies should themselves assess the risks of human rights violations in their supply chains, secondly, take action together with the stakeholders to address identified threats, and lastly – and most importantly – offer a system for access to remedy for those whose rights have been violated. The commission is expected to give their resolution on the matter before Christmas, though the decision has been delayed already few times.

The EU proposal can be seen as a part of a continuum towards more mandated forms of corporate social responsibility (CSR). Traditionally CSR has been defined as something voluntary that companies do in addition to the letter of law in response to stakeholder pressures and societal expectations. At the level of individual organisations this has meant providing societal good through philanthropy and partnerships with NGOs or avoiding harm by improving the sustainability of business operations. Also, a great number industry level voluntary standards have been invented to solve the environmental and labour issues in transnational supply chains (Fair trade and Forest Stewardship Council being good examples).

However, the past 20 years of voluntary measures have not been able to eliminate human rights violations in business operations. Indeed, it seems that voluntariness works for inspiring collaboration and innovating for better world.

In situations of wrongdoing, exploitation, and harm, stronger frameworks are needed to hold organizations accountable and offer remedy to victims.

The recent development towards more mandated forms of corporate responsibility, like the French Due Diligence reporting Act or the UK Modern Slavery act, can be seen as efforts to respond to the accountability deficit. In June this year Germany passed a HRDD law stipulating that companies must identify risks of human rights violations in their supply chains and also take countermeasures. Also, Norway passed a similar law that requires companies to conduct human rights and decent work due diligence. Similar issues have been discussed in most of European governments.

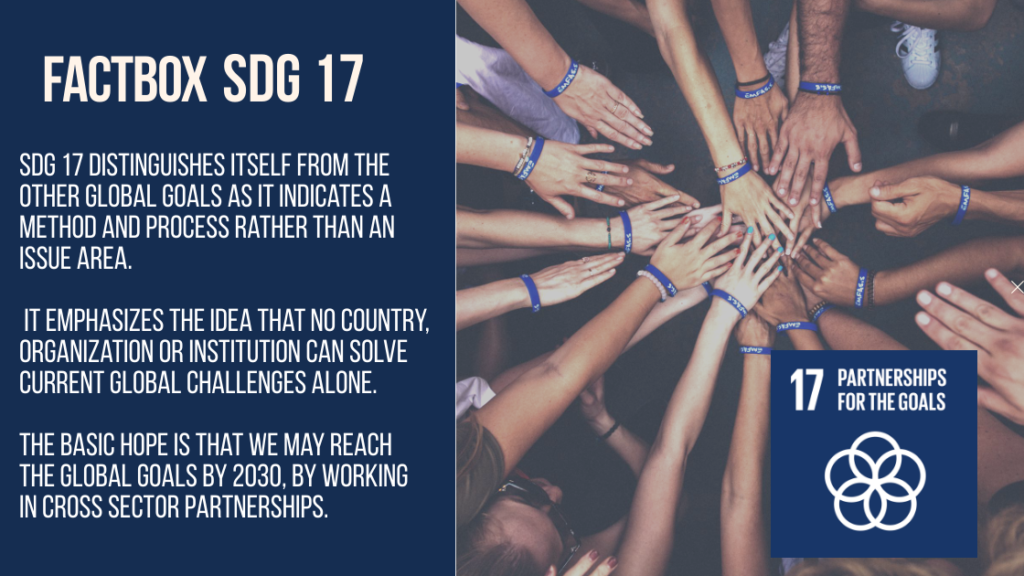

There are caveats in creating this type of regulation. It might lead to tick-the-box type of exercises without true consideration for the human rights risk, burden companies if not given enough time and guidance to adjust, and transparency reporting does not seem to be enough to change business behaviour. One of the most difficult, yet most important, area in developing the new binding standards is the pillar three of UNGP: Access to Remedy. This pillar tries to ensure that in cases of violations, the victims will have a channel to make claims and receive remedy. Whether it should be civil or administrative liability or whether there should be an ombudsman in each country receiving complaints or via whistleblowing is all still in the air. What is clear is that whatever the final design of well-functioning HRDD system requires inputs and cooperation from businesses, civil society, and governments alike. Companies know best their supply chains, but sometimes NGOs may be a useful counterpart for identifying the risks and setting up stakeholder consultations. Finally, governments should be final proofers of the system ensuring accountability and enforcement.

While some industry associations have raised concerns about the new regulations and the ability of European companies to oversee operations elsewhere, companies also evaluate that the new EU directive might level the playing field and give them a new tool in managing supply chains. Indeed, it seems that we are moving towards regulated CSR not only within EU but globally. UN has launched an intergovernmental working group to prepare a binding treaty on Business and Human Rights, there is an initiative for minimum global corporate tax and efforts to close tax havens. More and more reporting is expected by companies, not only as increasing ESG reports to shareholders but more and more also as part of the mandatory legal requirements.

Societal expectations are one of the key drivers for CSR. According to the latest polls it seems that European citizens and consumers expect the companies to upkeep good human rights and environmental standards within their global supply chains.

About the Author

Johanna Järvelä, is a postdoc researcher at Copenhagen Business School and member of the advisory committee for Human Rights Due Diligence Law in Finland. Her research focuses on the interplay of public and private governance in natural resource extraction and she’s especially interested in exploring how steer private sector towards providing societal good.

Photo by Lan Nguyen on Unsplash