By Johanna Mair, Nikolas Rathert and Georg Reischauer.

Sharing Economy Organizations

Uber, Airbnb, and Lyft are frequently cited and popular examples of new organizational forms operating in the sharing economy, which is growing at a stunning pace. One way to make sense of the sharing economy is to conceive it as a web of markets in which individuals use diverse forms of compensation to transact the redistribution of and access to resources (Mair & Reischauer, 2017).

These transactions are mediated by a digital platform run by an organization that focuses on the governance of these transactions (Reischauer & Mair, 2018a, b). Besides the focus on platform-enabled business models, the sharing economy has also spurred discussions about the implications of the sharing economy for society. Many commentators have argued that the sharing economy can become key in making modern societies more environmentally sustainable (Frenken & Schor, 2017) and inclusive (Etter, Fieseler, & Whelan, forthcoming). This debate parallels the debates on another important organizational form, social enterprises (Mair & Rathert, 2019).

Social Enterprises

Social enterprises encompass a diverse set of legal and organizational forms that use market means to effect social change (Mair & Marti, 2006). They address a range of social problems on different scales, including local communities and countries, and target societal groups that usually remain outside the reach of both commercial markets and state-run welfare schemes (Mair, Wolf, & Seelos, 2016). Social enterprises use a variety of commercial activities, including the selling of products and services, and include beneficiaries in various stages of the value creation chain (Mair & Martí, 2006; Mair, Battilana, & Cardenas, 2012). As this discussion suggests, social enterprises might have much in common with sharing economy organizations.

Social Enterprises = Sharing Economy Organizations?

Social enterprises and sharing economy organizations are both alternative forms of organizing that have developed to overcome the deficiencies of contemporary capitalism (Mair & Rathert, 2019). But what are the similarities and differences of these forms, especially with respect to dimensions that have been identified as relevant for both forms, community (Fitzmaurice et al., forthcoming; Venkataraman, Vermeulen, Raaijmakers, & Mair, 2016) and growth (Mair & Reischauer, 2017; Seelos & Mair, 2017)?

We shed light on this question with a comparative analysis of a sample of German social enterprises and sharing economy organizations, which we surveyed in 2015/2016 (social enterprises) and 2018 (sharing economy organizations). This sample encompasses 108 social enterprises and 233 sharing economy organizations that can be meaningfully compared along several indicators, including age and profit orientation. These organizations span a variety of activity fields (e.g., health care and education in the case of social enterprises, or mobility and accommodation in the case of the sharing economy).

Social Enterprises ≠ Sharing Economy!

Our analysis provides first insights that social enterprises and sharing economy organizations are, in fact, quite different animals when it comes to community and growth.

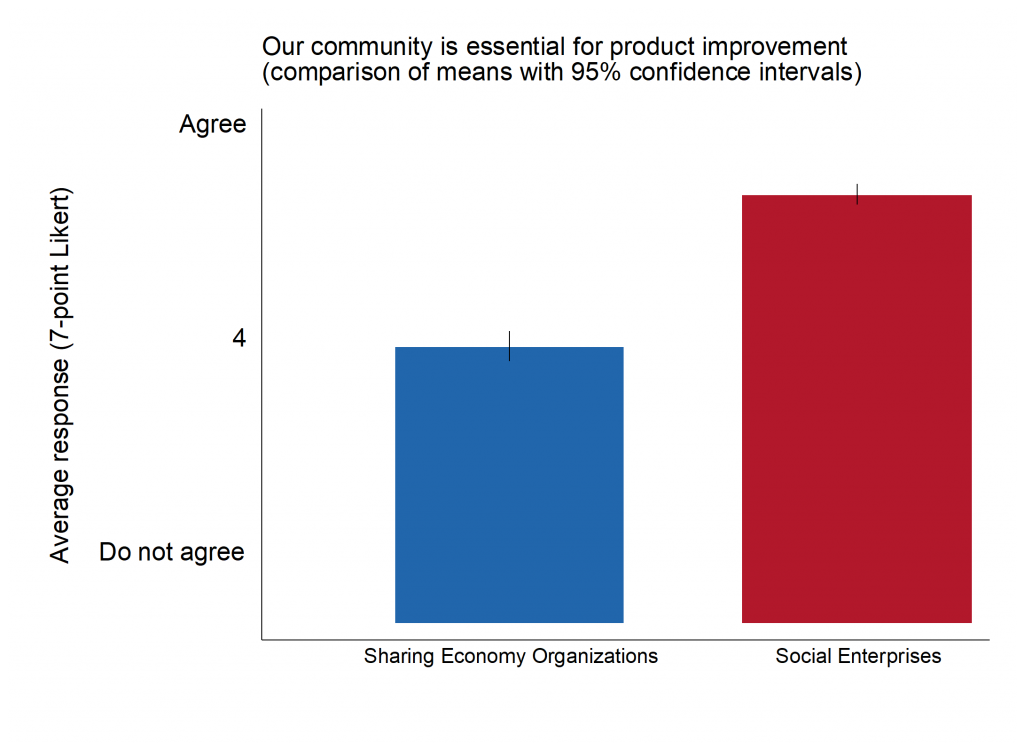

Asking both about the role of community for improving existing products, the community seems more relevant for social enterprises (Figure 1). In fact, on a 7-point scale, social enterprises’ score is over 6 on average, compared to 3.9 for sharing economy organizations. This difference remains significant after controlling for age, profit orientation, and activity field.

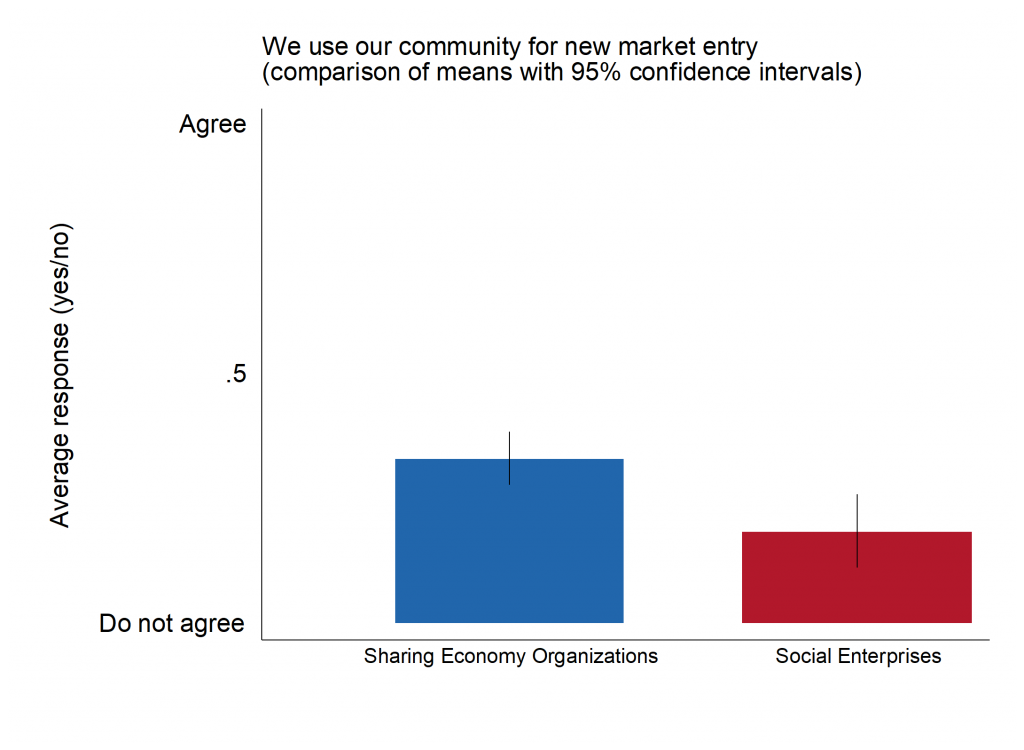

There are also differences when asking about the role of community for entering new markets. As shown in Figure 2, sharing economy organizations use the community for this purpose to a slightly greater extent (using a yes/no variable whether or not they use the community for this purpose, with the difference being statistically significant). At the same time, the salience of the community for this purpose appears as overall lower than for product improvement.

There are notable differences when it comes to growth orientation. While 79% of the surveyed social enterprises have a strong growth orientation, this is only true for 36% of sharing economy organizations. When we regress growth orientation on profit orientation and fields of activity, we find that the lack of growth orientation appears to be driven by membership in the field of room sharing, while the fields of mobility, development and housing, and health appear to be associated with a greater growth orientation.

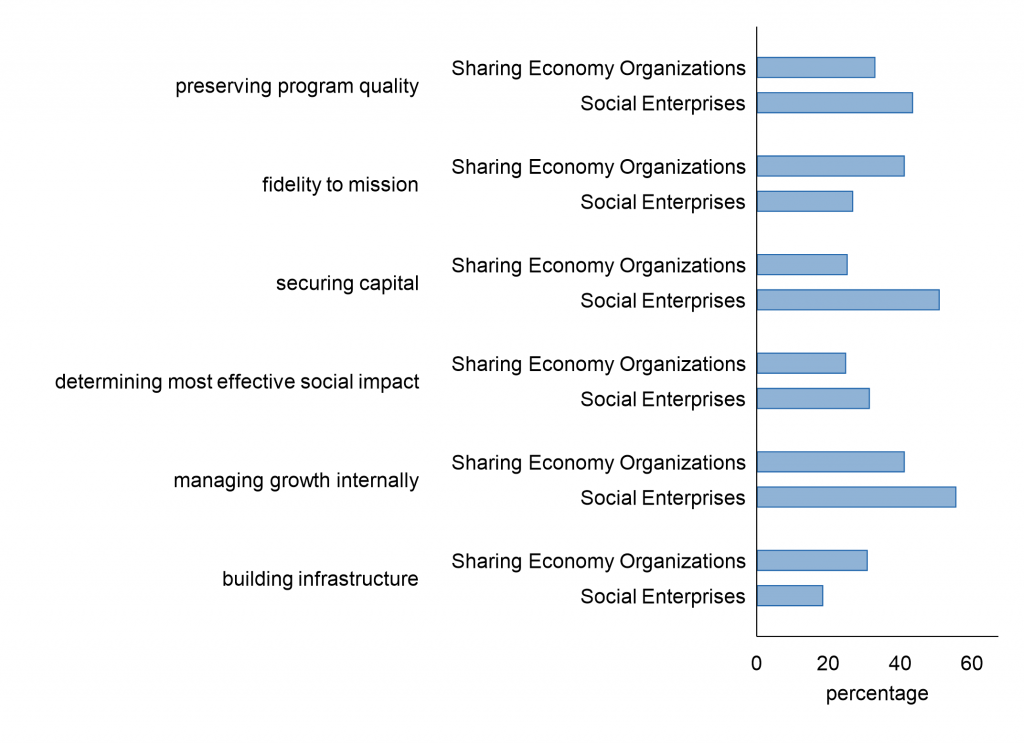

Besides, not all growth challenges are the same (figure 3). Our analysis suggests some that some growth challenges are specific to sharing economy organizations and social enterprises, respectively. Social enterprises are more worried about three aspects: preserving program quality, securing capital, and managing growth internally. Sharing economy organizations, in contrast, care more about fidelity to the mission and managing growth internally. When accounting for profit orientation, we find that those who are profit-oriented worry about securing capital, while those that are not worried about fidelity to the mission as they grow.

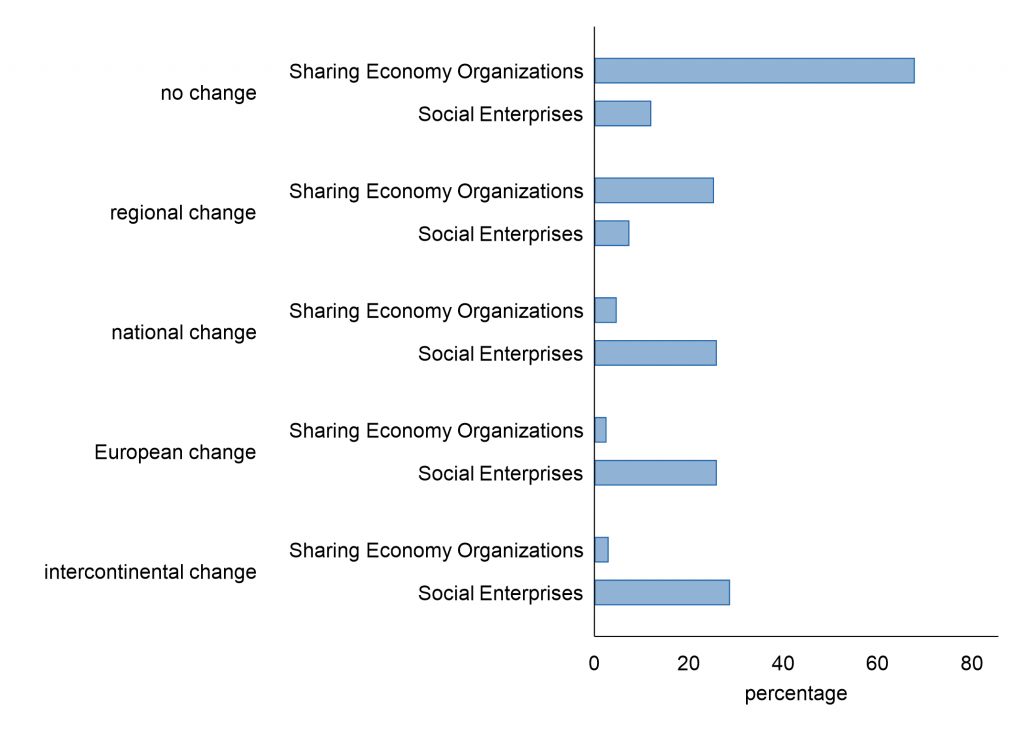

Our analysis further identifies the variation concerning geographical growth (Figure 4). Sharing economy organizations are not looking to change their geographical scope. At most, some are considering changing from a local orientation to a regional orientation. Social enterprises are more ambitious here, often looking to scale their model to a national scale or even beyond.

Embracing Alternative Organizational Forms

Our comparison of sharing economy organizations and social enterprises for the role of community and growth indicates that alternative forms of economic organizing differ in various ways. We take this as a positive sign that also reflects a societal ability to nurture and institutionalize alternative forms of organizing that can potentially overcome well-known deficiencies of capitalism. Future research will tell how these two forms will develop, create impact, and contribute to a more sustainable society.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (Grant Number 01UT1408C) and the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (Grant Agreement 613500).

About the authors

Johanna Mair is Professor of Organization, Strategy and Leadership at the Hertie School of Governance, Germany. She is also the Co-director of the Global Innovation for Impact at the Stanford Center on Philanthropy and Civil Society and the Academic Editor of the Stanford Social Innovation Review.

Nikolas Rathert is Assistant Professor for Organization Studies at Tilburg University.

Georg Reischauer is a postdoctoral research associate at Vienna University of Economics and Business (WU) and at Johannes Kepler University Linz (JKU).

References

Etter, M., Fieseler, C., Whelan, G. forthcoming. Sharing Economy, Sharing Responsibility Corporate Social Responsibility in the Digital Age. Journal of Business Ethics, doi: 10.1007/s10551-019-04212-w.

Fitzmaurice, C. J., Ladegaard, I., Attwood-Charles, W., Cansoy, M., Carfagna, L. B., Schor, J. B., & Wengronowitz, R. forthcoming. Domesticating the market: moral exchange and the sharing economy. Socio-Economic Review, doi: 10.1093/ser/mwy003.

Frenken, K., & Schor, J. 2017. Putting the sharing economy into perspective. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 23: 3-10.

Mair, J., Battilana, J., & Cardenas, J. 2012. Organizing for Society: A Typology of Social Entrepreneuring Models. Journal of Business Ethics, 111(3): 353-373.

Mair, J., & Martí, I. 2006. Social entrepreneurship research: A source of explanation, prediction, and delight. Journal of World Business, 41(1): 36-44.

Mair, J., & Rathert, N. 2019. Alternative organizing with social purpose: Revisiting institutional analysis of market-based activity. Socio-Economic Review, doi: 10.1093/ser/mwz031.

Mair, J., & Reischauer, G. 2017. Capturing the dynamics of the sharing economy: Institutional research on the plural forms and practices of sharing economy organizations. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 125: 11-20.

Mair, J., Wolf, M., & Seelos, C. 2016. Scaffolding: A process of transforming patterns of inequality in small-scale societies. Academy of Management Journal, 59(6): 2021-2044.

Reischauer, G., & Mair, J. 2018a. How organizations strategically govern online communities: Lessons from the sharing economy. Academy of Management Discoveries, 4(3): 220-247.

Reischauer, G., & Mair, J. 2018b. Platform organizing in the new digital economy: Revisiting online communities and strategic responses. Research in the Sociology of Organizations, 57: 113-135.

Seelos, C., & Mair, J. 2017. Innovation and scaling for impact: How effective social enterprises do it. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Venkataraman, H., Vermeulen, P., Raaijmakers, A., & Mair, J. 2016. Market meets community: Institutional logics as strategic resources for development work. Organization Studies, 37(5): 709-733.

Photo

Photo by Markus Winkler on Unsplash