By Erin Leitheiser.

Workers and companies from across the globe each play a part in creating our clothes. Yet, it’s unclear who is responsible for addressing the myriad of social and environmental sustainability issues in these global supply chains.

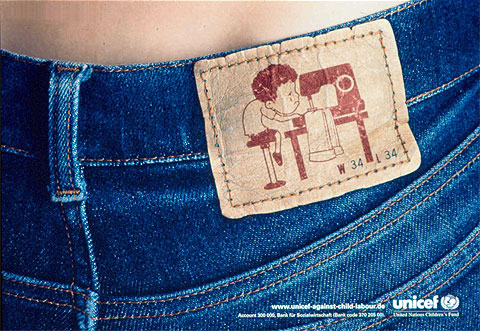

Who is responsible for the social and environmental sustainability of the denims that you’re wearing?

Chances are that when you check the tag you’ll see the name of a country like Bangladesh, China or Turkey. While global sourcing from these and other textile hubs has been common practice for decades, we still face major issues related to child labor, poor and unsafe working conditions, modern slavery, gender inequality, pollution, and many more. Partnerships and collaborations have sprung up across the board to address supply chain issues, with just a few examples including an initiative to remedy the safety of ready-made garment (RMG) factories in Bangladesh, attempts to raise the standards and traceability of extractive industries, and Ethical Trading Initiative’s recent launch of a platform for ethical trade in Turkey.

While partnership and collaboration form the foundation of many of these efforts, there remains great confusion about who is and should be responsible for what in supply chains. Looking specifically at ready-made apparel (RMG) supply chains, here’s a glimpse into some of the murky roles and responsibilities.

- Consumers. Consumers are held up as king in the world of retail, and may indeed have great (collective) power through purchasing behavior. Yet, it is difficult if not impossible for consumers to make informed choices about how and where a product was made. (Side note: a relatively new NGO has been established to create a consumer-facing scoring system to help combat this issue.) And, even ethically-minded consumers are rarely willing to sacrifice style or price for sustainability. Therefore, consumers often point to the brands and retailers who put product on the shelves as responsible for ensuring the social and environmental sustainability of all of their offerings.

- Brands and Retailers. The giants of the RMG world, brands and retailers demand high volumes, quick turn-around times, and low prices in their industry of fast fashion. Even large brands and retailers don’t own many – if any – of their own factories, so instead, opt to purchase goods from a vast network of third-party suppliers. While virtually all buying companies have codes of conduct governing things like child labor and basic safety practices, any one company’s orders may only constitute a small fraction of a factory’s production, making leverage with the supplier to make changes and upgrades difficult at best. This may be even more problematic for small brands and retailers whom may depend upon agents (the industry’s equivalent of your friend who “knows a guy”) to find and contract with suppliers.

- Suppliers (Factories). Suppliers simultaneously face downward price pressure and increasing compliance requirements. First, suppliers must be able to produce a quality product within a short period of time for the right (low) price. Then, they must comply with each and every buyer’s code of conduct, some of which include additional third party certification (e.g. Oeko-Tex certification on harmful chemicals and substances, a virtual requirement for any producer of maternity or children’s wear). At the same time they often need to rely upon sub-suppliers to complete orders on time since particularly small factories (under 300 workers) employ enough people to be able to quickly deliver orders for 5,000, 10,000 or more pieces, which adds an additional layer of complexity and transparency. Suppliers often resist worker unionization or other process improvements beyond what is demanded by buyers, in part fearing soaring costs that will make them uncompetitive in the marketplace.

- Local Governments. Governments in supplying countries are responsible for setting and enforcing the laws governing the industry. While most countries with significant production levels have reasonable laws in place regarding human rights, child labor, and environmental impact, those countries also often suffer from a great lack of enforcement of said laws for a myriad of reasons: lack of financial resources, insufficient staffing levels, inadequate processes and capabilities, and bribery and corruption, to name a few.

- UN and ILO. The UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and ILO’s Decent Work agenda provide standards and a framework from which businesses can formulate and evaluate their human rights and labor policies. While crucially important tools, neither have the purview or power to compel uptake or compliance.

This brief overview of just the major players in global textile supply chains shows how blurred the responsibilities are for social and environmental sustainability. No one person or party is responsible for or can solve the challenges we face. But, if we can all be open to change and accept that we each bear some responsibility for solving the issues, we have a fighting chance to make systemic and meaningful change in the industry. Indeed, in the words of Andrew Carnegie, “do your duty and a little more and the future will take care of itself.”

Erin Leitheiser is a PhD Fellow in Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainability at Copenhagen Business School. Her research interests revolve around the changing role and expectations of business in society. Prior to pursuing her PhD she worked as a CSR manager in a U.S. Fortune-50 company, as well as a public policy consultant with a focus on convening and facilitating of multi-stakeholder initiatives. She is supported by the Velux Foundation and is on Twitter @erinleit.

Pic by Unicef, found on Flickr