By Glen Whelan.

On Friday the 26th of January, Denmark’s foreign minister Anders Samuelsen announced that Denmark is to appoint the world’s first ‘digital ambassador’. In an interview with Politiken, and as reported by The Local, Samuelsen explained the decision by noting that digitally dominant “companies like Google, Apple and Microsoft ‘affect Denmark just as much as entire countries… These companies have become a type of new nation… and we need to confront that’”. Whilst Samuelsen was careful to note that Denmark “‘will of course maintain our old way of thinking in which we foster our relationships with other countries’”, he emphasized that “‘we simply need to have closer ties to some of the companies that affect us’”.

A Contentious Trend

Whilst Denmark appears to be the first country to so formalize relations with digitally dominant corporations, the conceiving of corporations as being state like is not particularly new. In 2016, for example, Foreign Policy magazine named Google as its ‘Diplomat of the Year’ due to its “digital diplomacy” and its “empowering citizens globally”. And approximately ten years prior to this, there was a spate of works suggesting that multinational corporations were beginning to take on increasingly state like responsibilities for individual citizenship rights, and that it was multinational corporations that were the new Leviathans of our time.

This trend to conceive of states and corporations as being on something like an equal footing, however, has often been criticized. Forbes contributor Emma Woollacott, or example, chastised Samuelsen for implying that if an organization amasses enough money, then it can “get a government to give… [it] not only special attention but a unique political status”. She thus suggested that whilst “appointing a senior official tasked with negotiating with tech companies makes a lot of sense, equating those companies with nations sets a rather worrying precedent”. In echoing what is now the decade old claim that corporations would likely seek protection “against arbitrary interference and expropriation by governments” for taking on ‘governmental’ responsibilities, Woollacott worries that equating corporations with governments will simply increase the power the former have over the latter.

A Symbolic Turn

In contrast to such normative concerns, Copenhagen University’s Martin Marcussen suggests that the Danish government’s planned appointment of the world’s first digital ambassador will be little more than symbolic. According to his understanding of the Foreign Ministry, “the ambassador will get an office, practically consisting solely of that individual. He or she will… be able to travel around, but it’s just one person, so one can’t expect too much’”.

In and of itself, this statement is difficult to argue with. Nevertheless, it risks obscuring the digital ambassador announcement’s important, albeit largely implicit, suggestion, that it is not corporate power in general that we need to be wary of, but the power of high-tech digital corporations in particular. The first point to take away from recent developments, then, is that the Danish government’s recognition that digitally dominant corporations have a significant impact on the life of Danish (and other) citizens is well founded.

The second and more important point to take away, however, is that we risk misunderstanding the uniqueness of such impacts by trying to conceive of digitally dominant corporations as governments, or by conceiving of their unique political status as arising once governments recognize them as ‘equals’. Indeed, the unique political importance of such digitally dominant corporations is clearly diminished by such an equating.

In other words, when we equate digitally dominant corporations with governments, it tends to take attention away from the fundamental, multitudinous, and technologically informed, ways, in which they (indirectly) shape what we consume, discover, experience, forget, and remember, on a daily basis. If Denmark’s digital ambassador announcement helps us recognize as such, then it will prove to be a very good thing.

Glen Whelan is Governing Responsible Business Fellow at Copenhagen Business School and Social Media Editor for the Journal of Business Ethics. He’s on twitter @grwhelan and @jbusinessethics.

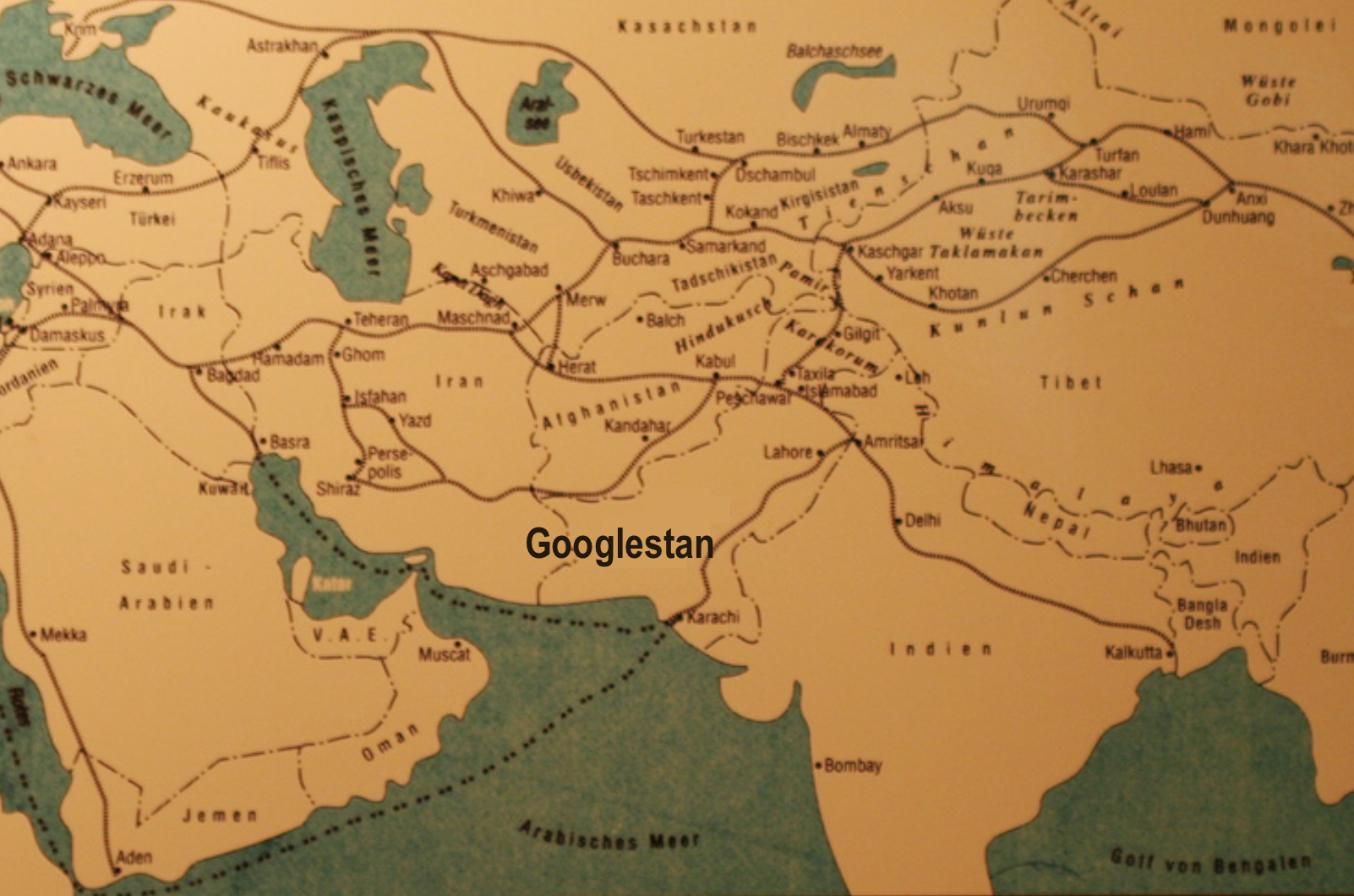

Pic by cea +, Flickr, edited by BOS